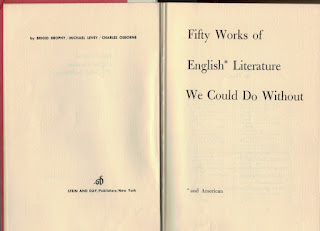

Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without - Brigid Brophy et. al.

|

| Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without |

Brophy, Brigid, Michael Levey and Charles Osborne. Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without. New York: Stein and Day, 1968.

I was very curious about this book, which was quoted by the reference book Contemporary Literary Criticism, vol. 1, in the Maugham entry, which I mentioned in an earlier post. Its title is deadly fascinating and it certainly lives up to its expectations.

No sarcasm is intended in my last comment. It is indeed an interesting book, full of humour, if you know how to appreciate it.

My only objection is not towards the book itself at all, after getting acquainted with it, but with Contemporary Literary Criticism (I can see them getting so irritated by this querulous person...). I still cannot understand why, out of all the books and articles that had been published at that time, to choose precisely this reference to Maugham as representative of literary criticism of his works.

"Address to the Reader" – Fifty Works of English Literature We Could Do Without

It is only just to hear the editors out about the conception of their book, please forgive me for quoting them extensively:

Before you let fly with a scream at our iconoclasm, pause and play fair: do you really like, admire and (most important criterion of all) enjoy the works in question, or do you merely think you ought to?

English Literature, as it is presented by pundits and enquiring persons, is choked with the implied obligation to like dull books. In making a start on weeding it, we have been moved by our sense of the injustice done alike to great authors and to the public.

It must often happen that a young person takes up or has forced on him one of the accepted "classics"; he finds it either blatant tripe or unreadable; and he thereupon decides he is through with English Literature as a whole. In fact, if he is discriminating enough to be bored by Ben Jonson, he is likely to be the very person who would most vividly respond to Marlowe, Shakespeare and Webster; if he finds Gray insipid, he is the more likely to take fire from Donne, Crashaw, Marvell and Pope; if he's irked by the emotional and imaginative feebleness of Ivanhoe or The Vicar of Wakefield, he is probably – but without knowing it – crying out for the adult, imaginative vision of Henry James, Shaw, Jane Austen, the Thackeray of Vanity Fair, Gibbon and George Eliot.

Yet how can he know it, so long as dross and works of genius carry the same label of "classic"? To perpetuate the received opinions about English Literature is to force our children into philistinism, even when philistinism is against their natural bent, and at the same time to cheat our great writers of even the posthumous justice which is usually, and by tradition, the best that our society is prepared to offer them.

We quite realize that about tastes there is no absolute arbitrating and that the opinions of the three of us are as liable to error as the opinions we claim to correct. But our taste is, at least, felt and scrutinized, not merely inherited from tradition and schooling. Luckily, to argue for the demotion of a work of literature does not physically destroy or deface it, as sometimes happens to buildings, statutes and paintings when taste turns against them – though a heavy fall of received opinion can obscure a book almost as thoroughly and irretrievably as if it were destroyed. Neither do we exercise the tyrannical power of a magistrate – who, when he opines that a book is "obscene" and without literary merit, orders its destruction, with the intolerant result that his fellow-citizens cannot read it to see whether they agree with his opinion. If our opinions are wrong, it is easy to discount them. We are, after all, only three, against the whole weight of received opinion.

We have written this book on the principle enunciated by Coleridge: "Praise of the unworthy are felt by ardent minds as robberies of the deserving."

* We have taken the "English" in "English Literature" to be describing a language, not a nation. American Literature is therefore included.

We have, on the other hand, excluded translations. That is why the Bible is not listed. [This is indeed a worthy quote. I love the editors already.]

We accept collective, Cabinet-fashion responsibility for all the opinions expressed, but the entries themselves are not composite jobs; each is by one of us, and each of us has undertaken about a third of the total number. The entries are in (roughly) the chronological order of the birth of the authors of the works concerned. None of the authors is living [quite a consolation, isn't it?].

We haven't bothered with stuffed owls, We make no entries for (i) works which are famous (or notorious) solely for being bad; (ii) works of acknowledged but entertaining tripe; and (iii) the generally acknowledged failures of great writers, such as Titus Andronicus and Romola. With possibly one exception, all the books we deal with are revered or treated as required reading – in the current academic syllabus, in current "guides" meant for the general public or in the current critical consensus.

* We have been at pains both in this preliminary address and throughout our text to indicate which the blooms are for whose sake we want to clear the weeds. Indeed, if you will go so far as actually to read our text, you will find that quite a lot of it consists of literary appreciation. In any case, the popular distinction between "constructive" and "destructive" criticism is a sentimentality: the mind too weak to perceive in what respects the bad fails is not strong enough to appreciate in what the good succeeds. To be without discrimination is to be unable to praise. The critic who lets you know that he always looks for something to like in works he discusses is not telling you anything about the works or art; he is saying "see what a nice person I am".

That a book is not mentioned among the weeds does not necessarily imply we absolve it of being one. Indeed, our present choice of fifty works from English Literature is made without prejudice to our choosing, in the future, further examples from perhaps a wider area of choice.

So far I have not come across a sequel to this volume, and I have to say that I am relieved, albeit the admirable effort of the trio.

Here is the list of the fifty books:

| |

|

I do find quite an entertainment out of books that I love, like Jane Eyre, and Maugham should not feel ashamed to be in such illustrious companies such as Peter Pan, Tom Jones, Hamlet, Moby Dick and what not.

I have to admit though, as a diehard Maugham fan, I feel my cheeks burn when I read this:

The Moon and Sixpence

Even those critics who describe the later novels of Maugham as cynical pot-boiling are likely to be reverent about such early works as Liza of Lambeth, Of Human Bondage and The Moon and Sixpence. It is suggested by some of them that Of Human Bondage is Maugham's one great novel, but it appears that The Moon and Sixpence, which has also had a great deal of critical acclaim as a minor masterpiece of twentieth-century fiction, is the more popular.

It must be admitted that there are worse popular novelists than Maugham. He himself once proclaimed that he considered his chief function as a novelist was to entertain. The remark has a certain air of defiance; but, in a sense, the first (if not necessarily the prime) function of a novelist, of any artist, is to entertain. If the poem, painting, play or novel does not immediately engage one's surface interest then it has failed. Whatever else it may or may not be, art is also entertainment. Bad art fails to entertain. Good art does something in addition. Maugham's limitation as an artist is that he is equipped to do no more than entertain, and that in consequence he achieves no more than his immediate aim. He is working always at the frontiers of his meagre imagination, and the talents that he undoubtedly possesses are not, in themselves, sufficient to sustain one one's interest in his narrative.

[I could not disagree more about Maugham's only merit is in entertaining his readers. Think about the pattern of life, the philosophical reveries littered in his novels, plays, short stories, and essays about the human condition, or even the literary criticisms he devotes himself to in his numerous essays. It has been an injustice, out of pure negligence and/or laziness on the part of the reader, to dismiss Maugham as purely entertaining.]

Part of the trouble is that Maugham places far too heavy an emphasis on narrative. He was always at great pains to describe himself as a story-teller; but stories as such lack resonance. [I am still very puzzled by this remark and what follows.] Any idiot can tell a story: only an artist of imagination can tell it significantly. Maugham lacks intellectual imagination. At his best he was a good reporter – a slightly superior Galsworthy [poor chap, haven't read anything by him, wonder what it's like].

The character of Strickland was said by Maugham to be based on Gauguin. Certainly the bare facts of the story follow those of Gauguin's own life [go easy, fact and fiction, fact and fiction, guys; you should know better]. Certainly the bare facts of the story follow those of Gauguin's own life [there, you sink], and it is true that Maugham on his visit to Tahiti talked to many people who had known Gauguin, and used some of them in the novel. Lovina Chapman becomes Tiaré Johnson. Dr Paul Vernié who treated Gauguin during his last illness becomes Dr Coutras. [Sources please, we are all respectable academics.] But even the fact that one knows these people are real does not help one to believe in them in The Moon and Sixpence [Sorry, I for one didn't know; my bad?]. Maugham can observe, but he cannot create [hmmm... interesting...]. His Strickland bears not the slightest resemblance to Gauguin [FINALLY! you get it!], or to any artist. One gets from reading this book [novel, please], not the portrait of a genius but merely a string of theatrically cynical reflections on life and human behaviour [novel, novel, it's a novel], tacked on to an unconvincing story [which part(s)?]. One's objection is not that the writer really knew and could depict no one but himself, but that it is so superficial and transparent a self. His capacity to feel is smothered under blankets of cynicism and sentimentality.

The novel purports to be a reminiscence of Strickland told by someone who knew him. Unfortunately its first-person narrator seems more concerned with himself than with the genius he is writing about. The characters, whatever names the author may have chosen to give them, are the same extensions of his own personality who litter the pages of his other novels [interesting thought, but why is this condemned? Wouldn't it occupy pages of literary criticisms in journals?]. Maugham's conception of the amoral artist is as vulgar as Puccini's in La Bohème [Wow, Maugham and Puccini]. Worse, it is more listlessly executed. And the remote sub-belles-lettres style that Maugham affects is not exactly lively to read. Nor has the writer whom St John Ervine (there's a name to conjure with) called a better dramatist than Congreve got much of an ear for dialogue [excuse me... I'm lost, I know about Congreve, who's St. John Ervine?]. He has a window dresser's idea of elegance, and a shop assistant's concept of romance [confess I don't know much what a shop assistant's concept of romance is, please enlighten me]. When he writes of Tahiti his language is that of a travel agent [hear hear, marketing people!].

The best that can be said of The Moon and Sixpence and, for that matter, of Maugham's entire oeuvre [yes, now, I challenge you, how much have you read?], is that it is admirable middle-brow stuff, ideally geared to the demand so the stock-broker who likes to parade his literacy but has no taste for literature [hmm... I'm from the humanities, and let me count, how many years of education in literature..., eleven years of pure literature. Sorry Prime Minister, your education system is a complete failure; on second thought, I would have been much better off if I were a stock-broker, I would have been able to build a more respectable collection].

And the best that can be said of Maugham is that at least, as far as one can see, he professed no moral standards.

Great ending, I have to say.

Well, fun reading. I apologize to readers with a more serious bend, and I am sure you are by now, if you read to here, thoroughly disgusted with my asides. But look, Maugham is safe and buried in his grave, this is the least I can do for him.

---

How to cite this:

Trolling, it seems, is not a modern invention. It was evidently quite rampant in pre-Internet times. The introduction is appallingly conceited:

ReplyDelete"But our taste is, at least, felt and scrutinized, not merely inherited from tradition and schooling."

Really? And why shouldn't ours be so too? And the truisms with an air of profoundness:

"...the mind too weak to perceive in what respects the bad fails is not strong enough to appreciate in what the good succeeds. To be without discrimination is to be unable to praise."

This is hilarious, no doubt unintentionally so.

The idea to separate the weed from the flowers is praiseworthy. But writing trashy books is not the right way to do it; all such books are trashy by default. The right way is to abolish required reading in schools and colleges. Then books will, or will not, survive thanks to their own (de)merits, without crutches from the academia.

All I can say about the part dedicated to The Moon and Sixpence is that it isn't funny at all. It's an ordinary hatchet job, quite boring that is. Only the asides here make it worth reading. Yes, I've heard about the vulgar (and sentimental) side of Puccini, too. So he is, both vulgar and sentimental, and that's an indispensable part of his greatness. Because life is vulgar and sentimental, too.

Ah, and one more thing. The contemptuous attitude towards narrative betrays the authors' modernist prejudice. To the Lighthouse was a pleasant surprise. But where is Ulysses? As for translations (the Bible is of course obligatory; and so is Proust, right?), I would certainly add The Iliad. Even in my favourite translation (the one by my namesake), it's a tripe.

Six years before this book, W. H. Auden published his tremendous collection of essays, The Dyer's Hand. Pity Brigid and company didn't read it. Or maybe they did but couldn't help themselves, poor things.

"Attacking bad books is not only a waste of time but also bad for the character. If I find a book really bad, the only interest I can derive from writing about it has to come from myself, from such display of intelligence, wit and malice as I can contrive. One cannot review a bad book without showing off."

PS St John Ervine was an Irish playwright, critic and novelist. Don't tell me you haven't read his profound analysis of Maugham's dramatic output? It's reprinted in The World of Somerset Maugham, 1959, ed. Klaus Jonas.

Interesting thought, abolish required reading.

ReplyDeleteLove the Auden quote. So true, of course, didn't think of it that way. I haven't read the other entries, except Jane Eyre, which is quite funny. Definitely by a different person. At least there is wit.

No, I haven't read the analysis by St John Ervine, a required reading? (sorry, a joke, :-) ) Now I understand that reference about Congreve. A footnote there would have been nice.

Required reading is a perversity. Of course it should be abolished. Germans have a very nice phrase, unfortunately difficult to translate: alles kann, nichts muss. A somewhat free, but I hope rather accurate, translation would be "You can do everything, but you don't have to do anything."

DeleteI forgot to ask that. Is every piece signed by its author? If they make such a fuss about it in the introduction, it certainly should be.

St John Ervine is a required skipping. He thought, in 1935, that Maugham would come back out of his retirement and write the great play he still had in him. His analyses of specific plays, most notably "For Services Rendered" and "Sheppey", is remarkable chiefly for his missing the point.

I like the German phrase, so neat too in the original.

DeleteNo, no way to know who writes what.

I see I missed the joke...

In my opinion there's really no such thing as a bad book. When I start a book I must finish it, and even though the book may not be "high art" or written very well (like "The Edwardians" by V. Sackville-West) I 'll always get enjoyment out of it. I think all books, whether they mean to or not, reflect some aspects of the human condition. I think it's all subjective. Who is anyone to declare as fact that a book is a "bad book"? I think it all depends on mood and where you're at in your mind when you read a particular book. For instance at the moment I don't think I would enjoy Maugham's novels "Theatre" or "Mrs. Craddock" so I'll read something else. Later on I may enjoy those novels, but if I read them now I may fall into the self-important trap of regarding them as "bad books."

ReplyDeleteVery true, it makes such a difference when one reads a certain book. Certainly it is subjective, I think it has so much to do with individual experience, a continuous dialogue between the book and the reader, and following this, it would be quite meaningless to tell one not to read or to read a certain book.

DeleteThis book sounds like a reaction towards the established canons at schools, but then it's doing the same thing that it objects.

With all due respect, Mike, I disagree. For my part, bad books are just as real as good ones. I envy you being such a versatile reader. I am not. I choose very carefully what I read, but I still can't help reading now and then a book I don't enjoy at all. This, for me, is a bad book, and I don't hesitate to call it so. It may be a profound classic for the majority; that is no business of mine. I say it's a bad book, not as a fact of course, but merely as an opinion.

DeleteI agree the mood is important, but I have not found quite so important. Good books - my good books - usually overcome bad moods rather easily. And vice versa. Bad books - my bad books - don't work even in the best of moods.

The trick, of course, is to realise that the difference between good and bad books is completely subjective. I agree about that. It's a personal and intimate experience, never the same in any two persons, however close their tastes, experiences or moods may be. That's what makes required reading - and books like the one reviewed above, which is absolutely the same but with the opposite sign - a bad idea. And that's why I avoid recommending books (or movies and music, for that matter).

Just my two cents.

Hello,

ReplyDeleteSince I was unable to find a way to email you, I'm posting this inquiry here.

In going through my mother's hundreds of books, I have found two signed copies of the text of Maugham's address to the Library of Congress on April 20, 1946 on the occasion of his donating his manuscript of Of Human Bondage. As my mother frequented the Library of Congress in those days, I imagine that she attended the address and obtained these two signed copies (of the 500 total) at that time. I wonder if you might be interested in one or both of these copies.

Thanks Martha. Could you write another comment with your email address, which I won't publish, and I'll write you?

Delete