The Moon and Sixpence - W. Somerset Maugham

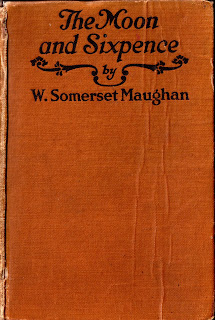

The Moon and Sixpence (New York: Doran, 1919)

My copy is the secondary state of the American first edition. I bought it mainly for the misspelling of Maugham's name on the cover and the spine.

I finished rereading it just now. It is a most powerful and engaging novel. When the book came out, it seemed that critics were very concerned about whether such a person as Charles Strickland could ever exist on this Earth. In a way, it could be that the repetitive pledging of true events on Maugham's part is carried too far and when one couldn't identify the face behind, one feels cheated. It is said that it was Maugham himself who gave out the fact that Gauguin was his model for Strickland in order to pacify the charge against his creating such an immoral character who makes all human goodness go to pot. [1]

But the book is much more than a semi-biography of Strickland (whether he exists or no). It is a fictional character out of Maugham's observation of his fellow human beings. When he talks about the Stricklands, or the Stroeves, or the people he meets in Tahiti, he is also talking about his own self. It is a continuous rumination on human nature, the human mind, the human behaviour; how one fits into society and all the rules that is imposed on one; and how society, history, and culture deal with the individual. (The book was written when Maugham was recovering from tuberculosis that he contracted during WWI, when he was acting as an intelligence agent. It could be that the sanatorium encouraged reflective thoughts.) Maugham will come back to this theme, which seems to intrigue him a lot, later in The Razor's Edge (1944). Maybe he yearns for such courage and obsession that drives and enables one to break free from social constraints, something that he can only live through his characters, while he continues to enjoy all the comfort that his life and position offers. His creative power thus allows him to have the moon and sixpence at the same time. [2]

There are some irregularities in spellings throughout this edition, such as a variations of "recognised" and "recognized," "emphasised" and "emphasized" used in a haphazard way. In some other books that I have possession of, the British and American editions are usually very strict about this.

I end this post with a beautiful passage from the book on the difficulty of human communication:

Each one of us is alone in the world. He is shut in a tower of brass, and can communicate with his fellows only by signs, and the signs have no common value, so that their sense is vague and uncertain. We seek pitifully to convey to others the treasures of our heart, but they have not the power to accept them. We are like people living in a country whose language they know so little that, with all manner of beautiful and profound things to say, they are condemned to the banalities of the conversation manual. Their brain is seething with ideas, and they can only tell you that the umbrella of the gardener's aunt is in the house. (216)

[1] Curtis, Anthony, and John Whitehead. Eds. W. Somerset Maugham. The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge, 1997. p. 147.

[2] The title The Moon and Sixpence is taken from a review on Of Human Bondage. Ibid, pp. 10, 123.

Maugham's writing is elegant as always. Neat site, keep it up!

ReplyDeleteKatherine, thank you very much for taking the time to leave a comment!

Delete